The UPSC on January 27 conducted interviews to appoint India’s next drug controller general of India (DCGI) – a crucial position.

The position of DCGI has gained even more prominence after the repeated incidents of poor manufacturing standards of Indian drugs, two highlighted internationally by Uzbekistan and Gambia. There are a lot of expectations that the “new DCGI” should clean the regulatory mess by his strong, scientific and non-bureaucratic approach.

The DCGI heads the drug regulatory landscape of India, including quality of medicines, medical devices and vaccines used in India apart from manufacturing, exports, imports, new drug approvals and clinical trials.

To give you an idea, it would not be inaccurate to say that the person holding this position is directly and indirectly responsible for all medical products consumed by us. The DCGI is head of the health regulatory agency, Central Drugs Standard Control Organisation (CDSCO).

The process of interviews is now over and the panel, as per sources, has recommended a final candidate. The UPSC will now recommend the candidate’s name to the appointments committee of the cabinet (ACC), which will finalise the selection.

Apart from regulatory flaws, failures and loopholes, there are two challenges that must be solved immediately:

‘TEAM SOMANI’ V ‘TEAM REDDY’ – AN INTERNAL CONFLICT

Dr VG Somani is the current DCGI and one of the three contenders for the same position once again. He was appointed for a term of three years on August 14, 2019. So far, he has already got two extensions – one in August and another in November 2021. His tenure is slated to end on February 15, 2022.

Before Somani, Dr Eswara Reddy – the joint drug controller – also served as DCGI from February 2018 to August 2019. He has been working at CDSCO for the past 23 years.

Under the Somani regime, multiple vaccines against Covid-19 and other therapies were approved and processes fast-tracked, whereas under Reddy’s regime, several critical laws were passed including the New Drugs and Clinical Trial Rules and Cosmetics Rules.

Both officers have a proven track record and are credited with several achievements. But much of the CDSCO seems to side with either.

What is intriguing, however, is that the divide is neither formally etched out nor dictated by the two officials. It is like the CDSCO staff has subconsciously decided to support one or the other.

This is a known fact for health reporters dealing with the CDSCO. When I speak to multiple officers and state regulators working under CDSCO, they admit to a cold war between the two groups and how it is affecting the performance of the organisation.

“The unconscious divide, unfortunately, hinders the organisation from performing in the interest of CDSCO as an organisation or in the interest of the nation. Instead, half of them celebrate when the other half fails,” they said.

While Reddy is not directly serving in CDSCO – after allegations of bribery and an ongoing court case – the divide still persists along with several other conspiracy theories floated by lovers and haters.

The new DCGI – even if it is Dr Somani again – needs to sort out internal chaos.

ONGOING POWER STRUGGLE BETWEEN CDSCO, STATES

The CDSCO is an arm of the union ministry of health and family welfare. Under the Drug and Cosmetics Act, the regulation of the manufacture, sale and distribution of drugs falls under the ambit of “state” authorities whereas “central” authorities are responsible for the approval of new drugs, clinical trials, laying down the standards for drugs, control over the quality of imported drugs among others.

The division of duties and responsibilities is clear under the rules, but somehow, the CDSCO is trying to take over duties of states without sharing enough power. Multiple state regulators I spoke to, before penning the column, told me that the trend of grabbing power from state regulators is creating confusion, which in turn, is making them insecure and inefficient.

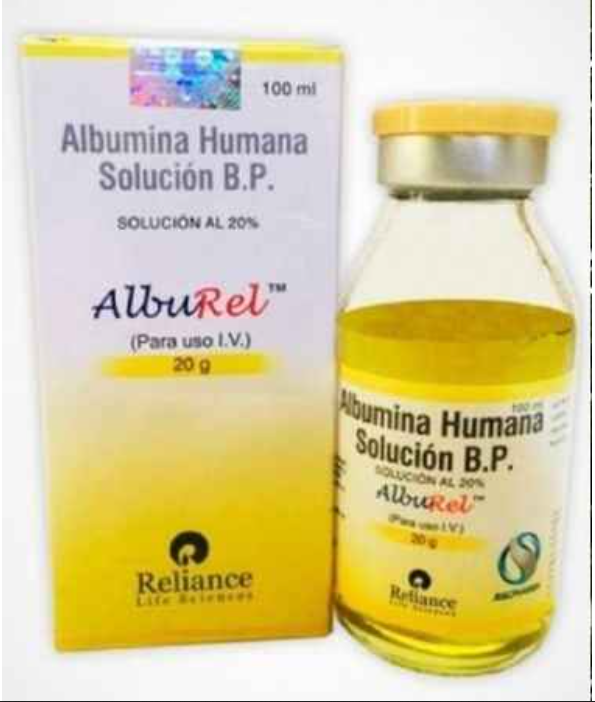

For instance: the CDSCO has now become the licensing authority or the dual licensing authority – where both state and central permissions are required – for several drug items such as blood banks, glucose, saline and IV fluids among others. It was earlier under the purview of states.

It is now the licensing authority for Class A and Class B medical devices, for which state regulators held the charge earlier. The CDSCO now gets its own central drug inspectors notified for the whole of India.

“It randomly deploys central drug inspectors to join inspections for the grant of licences by the state regulators without any locus standi,” said a former state regulator over a long phone call.

A drug inspector working for a large state blamed the CDSCO for coining a new term called ‘risk-based inspections’, which are done by their inspectors.

“The CDSCO sends inspectors for inspections following which they send the inspection reports to state regulators for further actions,” the drug inspector said. “But under the law, state regulators are not bound to follow instructions from CDSCO inspectors. Even courts have now started asking this question. It creates confusion on what orders should be followed and why.”

With this trend, state officers are becoming anti-CDSCO. “When some mishap happens, CDSCO puts everything on the state regulators despite being part of most of the investigations and audits,” the person added.

In short, states have “responsibility” but not “power” whereas the CDSCO has “power” but no “responsibility”.

I can go on detailing the cavities that the country’s apex health regulator needs to fix. But settling the two issues mentioned above could be a good start.